24.11 — 20.1 24

-

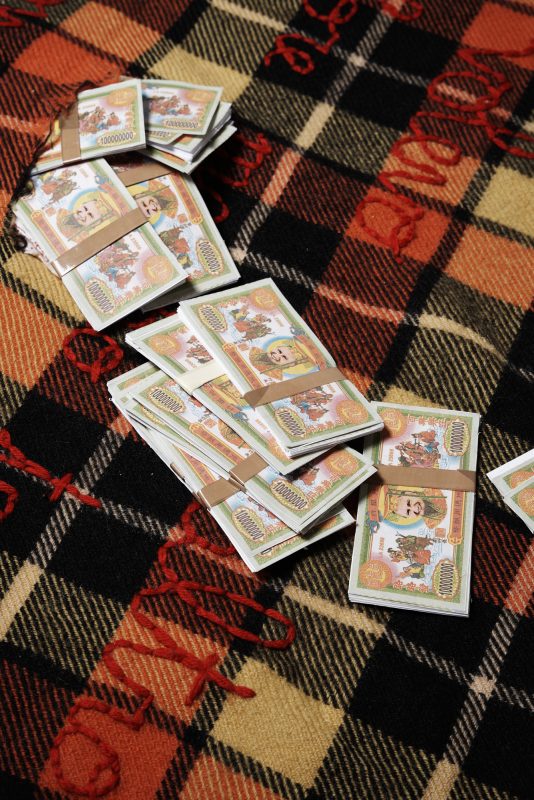

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

Hôtel-Dieu Installation view

-

Une Salle de L'Hôtel-Dieu au XVI Siècle

Une Salle de L'Hôtel-Dieu au XVI Siècle

-

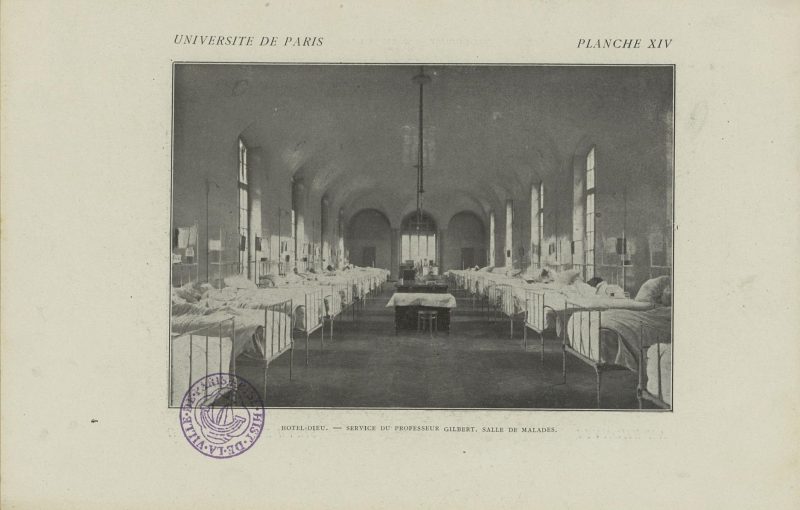

Hôtel-Dieu, Paris, Casimir, 1892

Hôtel-Dieu, Paris, Casimir, 1892

-

Hôtel-Dieu, Paris

Hôtel-Dieu, Paris

-

Homeless shelter Ratcliff London 1901

Homeless shelter Ratcliff London 1901

24.11 — 20.1 24

The name Hôtel-Dieu meant in the Middle Ages the biggest accommodation in town. It was free for the poor and the rich were asked to pay for their stay. These old European institutions were intended to host the homeless and the needy as well as travellers of any sort. Religious orders run them in a tradition of kindness. It was a place of hospitality and prayer, combined with a not so much hidden agenda of evangelization. It then also served as a hospital, but the idea of a single place reserved for medical care only, did not exist yet. You can call it a big medieval Inn, providing also housing. Only by the 16thcentury, admissions shifted slowly to the chronically ill exclusively. You might give a look at Michel Foucault’s writings to get, a maybe more sinister, but also clearer picture of how medical institutions were established throughout time.

The philosophy of a Hôtel-Dieu, of innkeeping in the Middle Ages as well as the philosophy of a contemporary art gallery today however goes more or less like this: “The poor man is happy when the rich has his fun”. And The Boheme — a word for the gipsies, who in 19th Century France came mostly from Bohemia, but in semantics is referring to the lifestyle of poets and artists, who mostly where coming from the middle and upper class — The Boheme, is, as Walter Benjamin comments in his Paris Exile on his escape from Nazi Germany, when looking back at the European past, The Boheme is: “the training ground for the artistic life; it is the steppingstone to the Académie, to the Hôtel-Dieu, or to the Morgue.”[i]

Poor people have fashions as little as they have a history, and their ideas, their tastes where rarely tracked down or passed through the Centuries. But in a Hôtel-Dieu you surely can find a glimpse of their aesthetics. It is here where you display the photograph, the drawing, the book, the letter, the pin up poster, the one thing you could save whilst everything else got lost or was stolen from you. Maybee it’s an angel-drawing from Paul Klee, or maybe a purely random item from your former household — but it is the object that still sticks with you. It’s only in a Hôtel-Dieu where you understand the true value of beauty and things.

The Hôtel-Dieu, a place of prayer and restoration in its beginnings, disintegrated in modern times more and more into the illuminated and scientifically organized hospital on the one hand, and into a refuge for the homeless of early Industrialization on the other. It later even decayed into the shelters for the unemployed and impoverished masses of the early 20th Century. In the Century prior to our current Millenium Charlie Chaplin has become the greatest Comic because he has incorporated into himself the deepest fear of his contemporaries — impoverishment. The 20th Century was a century where there was a ban on Puppet-Theatre in Italy and a ban on Chaplin Films in the III. Reich, because every puppet could put on Mussolini’s chin and every inch of Chaplin could expose the shabbiness of the Führer.[ii]

One of these homeless shelters in which the Hôtel-Dieu decayed, while big modern hospitals were established like foretelling’s for the logistic needs of the coming World Wars, was the Männerwohnheim in the Meldemannstrasse in Vienna. “In Autum of 1909”, Reinhold Hanisch writes in The New Republic in April 1939: “the neighbour on my right looked sad, and so we asked him questions. For several days he had been living on benches in the park where his sleep was often disturbed by policemen. He had landed here dead tired, hungry, with sore feet. His blue-checked suit had turned lilac. He came to Vienna in the hope of earning a living here, since he had already devoted much time to painting in Linz but had been bitterly disappointed in his hopes…The next day he was planning a new project. He had seen The Tunnel, a picture made from a Novel by Bernhard Kellermann, and he told me the story. An orator makes a speech in a tunnel and becomes a great popular tribune. He had success with the people in the Männerwohnheim, for they were always ready for fun, and he was a sort of amusement for them”.[iii]

“As long as there is still one beggar, there will still be myth” is another famous saying of Walter Benjamin. Looking back at the 20th Century a common thread characterized it’s first half: The most progressive Aesthetics for the crowds, as clearly visible in Chaplin’s gestures, or the adventures of poor Mickey Mouse and unlucky bigmouth Donald, was completely trusting on the topos of the unemployed tramp. The disinherited and clueless masses were performing in the first half of our past Century in the allegoric Avatars of a Mouse, of a poor beggar, or of a Duck, in front of the camera, and the public was caught with liberating laughter looking in that mirror on the screen. Chaplin’s and Walt Disney’s aesthetics knew that the crowd instinctively understood and perceived perfectly in their flesh what systematic impoverishment means for their lives. The same was true for the regressive Aesthetics of fascism. Both Hollywood and National socialism drawn in their own way their inspirations and propellant from the fear of impoverishment, from the fear of being dismembered, diminished, left with no traditions and no identity and cut to pieces by the machinery of the Modern Times. The social reality was at that time for most people the life of the unemployed tramp, the reality of social injustice and the systematic unfair distribution of wealth.

History never repeats itself as already Søren Kierkegaard knew. History comes always with an interesting and surprising twist. But still today racism is not only a mental or linguistic condition. Racism is also grounded in economic realities and probably still today, like in the Weimar Republic and in almost every case in human history, a result of the systematic unfair distribution of wealth in a society over a too long period of time, a result of a methodical and unfair socialization of losses and privatization of profits. Also, civil war and war between nations is mainly grounded in these reasons. Still today the spectre haunting the Globe, is the fear of private or nationwide economic failure, the fear of mass immigration, the fear of the climate and global atmosphere changing for the worse, the fear of a strange physical and spiritual disease infecting us all in the future. And still today Art needs to play with Mythology in order to exist, and one global ambiguous myth to play with, is surely the Hôtel-Dieu. It’s in these weeks, before and after Christmas 2023, that we want to dedicate an exhibition in A plus A Gallery to this myth.

[i] Walter Benjamin, Arcades Project, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, p. 585

[ii] Walter Benjamin, Hitlers Diminished Masculinity. In: Selected Writings vol 2, part 2, edited by Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland and Gary Smith, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, p. 792

[iii] Reinhold Hanisch, I was Hitlers Buddy. In : The New Republic, April 5, 1939

—————————- ITA —————————————————

Il nome Hôtel-Dieu significava nel Medioevo il più grande alloggio della città. Era gratuito per i poveri, mentre ai ricchi veniva chiesto di pagare per il loro soggiorno. Queste antiche istituzioni europee erano destinate a ospitare i senzatetto e i bisognosi, nonché i viaggiatori di ogni genere. Gli ordini religiosi li gestivano secondo una tradizione di gentilezza e misericordia. Si trattava di un luogo di ospitalità e di preghiera, unito a un programma non tanto nascosto di evangelizzazione. Serviva anche come ospedale, ma non esisteva ancora l’idea di un luogo unico riservato alle sole cure mediche. Si può definire una grande locanda medievale, che forniva anche alloggi. Solo a partire dal XVI secolo, gli ospiti, sempre di più, erano ricoveri di malati cronici. Si potrebbe dare un’occhiata agli scritti di Michel Foucault per avere un quadro forse più sinistro, ma anche più chiaro, di come le istituzioni mediche sono state create nel corso del tempo.

La filosofia di un Hôtel-Dieu, della gestione di una locanda nel Medioevo, così come quella di una galleria d’arte contemporanea oggi, è più o meno questa: “Il povero è felice quando il ricco si diverte”. E la Bohème – parola che indica i gitani, che nella Francia del XIX secolo provenivano per lo più dalla Boemia, ma che nella semantica si riferisce allo stile di vita di poeti e artisti, che provenivano per lo più dalla classe media e alta – è, come commenta Walter Benjamin nel suo Esilio parigino e in fuga dalla Germania nazista, guardando al passato europeo, la Bohème è: “la palestra della vita artistica; è il trampolino di lancio verso l’Académie, l’Hôtel-Dieu o la Morgue”.[i]

La gente povera non ha una moda così come non ha una storia, e le sue idee, i suoi gusti sono stati raramente rintracciati o trasmessi attraverso i secoli. Ma in un Hôtel-Dieu si può sicuramente trovare un assaggio della loro estetica. È qui che si espone la fotografia, il disegno, il libro, la lettera, il manifesto, l’unica cosa che si è stato in grado di salvare, mentre tutto il resto è andato perduto o ci è stato rubato. Magari è un disegno di Paul Klee con un angelo, o forse un oggetto puramente casuale della nostra vecchia casa, ma è l’oggetto che ti è rimasto e sta con te. È solo in un Hôtel-Dieu che si capisce il vero valore della bellezza e delle cose.

L’Hôtel-Dieu, luogo di preghiera e di restauro alle origini, si è disintegrato in epoca moderna trasformandosi sempre più in un ospedale illuminato e scientificamente organizzato, da un lato, e in un rifugio per i senzatetto della prima industrializzazione, dall’altro. In seguito, si è addirittura trasformato in un ricovero per le masse disoccupate e impoverite del primo Novecento. Nel secolo precedente al nostro attuale millennio Charlie Chaplin è diventato il più grande comico perché ha incorporato in sé la paura più profonda dei suoi contemporanei: l’impoverimento. Il XX secolo è stato un secolo in cui c’è stato il divieto del teatro dei burattini in Italia e il divieto dei film di Chaplin nel III. Reich, perché ogni marionetta poteva mettere in mostra il mento di Mussolini e ogni centimetro di Chaplin poteva mettere a nudo la squallidezza del Führer.[ii]

Uno di questi rifugi per senzatetto in cui l’Hôtel-Dieu decadeva, mentre venivano costruiti grandi ospedali moderni come annunci per le esigenze logistiche delle prossime guerre mondiali, era il Männerwohnheim nella Meldemannstrasse di Vienna. “Nell’autunno del 1909”, scrive Reinhold Hanisch su The New Republic nell’aprile 1939: “il vicino alla mia destra aveva un’aria triste e così gli facemmo delle domande. Da diversi giorni viveva sulle panchine del parco, dove il suo sonno era spesso disturbato dai poliziotti. Era arrivato qui stanco morto, affamato, con i piedi doloranti. Il suo vestito a quadri blu era diventato lilla. Era venuto a Vienna nella speranza di guadagnarsi da vivere qui, dato che aveva già dedicato molto tempo alla pittura a Linz, ma le sue speranze erano state amaramente deluse… Il giorno dopo stava pianificando un nuovo progetto. Aveva visto Il tunnel, un film tratto da un romanzo di Bernhard Kellermann, e mi raccontò la storia. Un oratore tiene un discorso in un tunnel e diventa un grande tribuno popolare. Aveva successo con gli abitanti del Männerwohnheim, perché erano sempre pronti a divertirsi e lui era una sorta di svago per loro”.[iii]

“Finché ci sarà un mendicante, ci sarà il mito” è un altro famoso detto di Walter Benjamin. Guardando al XX secolo, un filo conduttore ha caratterizzato la sua prima metà: L’estetica più progressista per la folla, come chiaramente visibile nei gesti di Chaplin, o nelle avventure del povero Topolino e dello sfortunato paperino (Il Donald) che fa la voce grossa, si affidava completamente al topos del barbone disoccupato. Le masse diseredate, sprovveduti e impreparate ai grandi cambiamenti in atto si esibivano nella prima metà del secolo scorso negli avatar allegorici di un topo, di un povero mendicante o di un papero, davanti alla macchina da presa, e il pubblico veniva colto da una risata liberatoria guardandosi nello specchio sullo schermo. L’estetica di Chaplin e di Walt Disney sapeva che la folla istintivamente comprendeva e percepiva perfettamente nella sua carne ciò che l’impoverimento sistematico significava per la sua vita. Lo stesso valeva per l’estetica regressiva fascista. Entrambi Hollywood e il Nazionalsocialismo traevano a loro modo ispirazione e propellente dalla paura dell’impoverimento, dalla paura di essere smembrati, sminuiti, lasciati senza tradizioni e senza identità e fatti a pezzi dalla macchina dei tempi moderni. La realtà sociale era a quel tempo per la maggior parte delle persone la vita del barbone disoccupato, la realtà dell’ingiustizia sociale e della sistematica e ingiusta distribuzione della ricchezza.

La storia non si ripete mai, come già sapeva Søren Kierkegaard. La storia si presenta sempre con una svolta interessante e sorprendente. Ma ancora oggi il razzismo non è solo una condizione mentale o linguistica. Il razzismo si fonda anche su realtà economiche e probabilmente ancora oggi, come nella Repubblica di Weimar e in quasi tutti i casi della storia umana, è il risultato di una sistematica e ingiusta distribuzione della ricchezza in una società per un periodo di tempo troppo lungo, il risultato di una metodica e ingiusta socializzazione delle perdite e privatizzazione dei profitti. Anche le guerre civili e le guerre tra nazioni si basano principalmente su queste ragioni. Ancora oggi lo spettro della paura che perseguita il mondo è la paura del fallimento economico privato o nazionale, la paura dell’immigrazione di massa, la paura che il clima e l’atmosfera globale cambino in peggio, la paura di una strana malattia fisica e spirituale che ci infetterà tutti in futuro. E ancora oggi l’arte ha bisogno di giocare con la mitologia per esistere, e un mito globale ambiguo con cui giocare è sicuramente l’Hôtel-Dieu. È in queste settimane, prima e dopo il Natale 2023, che vogliamo dedicare una mostra in galleria A plus A a Venezia a questo mito.

[i] Walter Benjamin, Arcades Project, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, p. 585

[ii] Walter Benjamin, Hitlers Diminished Masculinity. In: Selected Writings vol 2, part 2, edited by Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland and Gary Smith, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, p. 792

[iii] Reinhold Hanisch, I was Hitlers Buddy. In : The New Republic, April 5, 1939